When our group of Canadian students signed up to learn about social movements in Brazil through Bishop’s University in Sherbrook, Quebec we were told we would meet various social movements including urban social movements headquartered in Sao Paulo. The last two days of our course was set aside for such visits. We would travel to the headquarters of the MST’s National Secretariat and meet the various leaders there. At the Escola Nacional Florestan Fernandes (ENFF) we were told that we would be meeting National leaders from the MST, MAB, Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragems (Movement of People Affected by Dams), ALBA Movimientos, and the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto (MTST, Movement of Workers Without a Roof). We were advised that shortly after meeting with the various group leaders that we would be visiting one of the biggest urban occupations in Sao Paulo, the Copa do Povo (People’s World Cup) in the East Zone of Sao Paulo.

On our first week in Sao Paulo I saw the MTST in action during the march against the Brazilian conglomerate Odebrecht. Their organization amazed me and their fervour during the march infused the rural MST activists with even more energy and passion for what they were doing. They distinguished themselves from the marchers by wearing red t-shirts with the MTST logo encircled on the back. They carried red flags, some with white lettering calling for urban reform others with their painted logo. The group carried out three simultaneous demonstrations on May 8th, 2014. Now we were getting ready to see some of them in their home setting.

May 23rd was long day for our group. We left early in the morning to avoid Sao Paulo’s notoriously bad traffic to meet with representatives from the four various organizations including the staff of the leading leftist newspaper Brasil De Fato and radio station Radio Agência. We learned of their history, their internal struggles and their successes at home and abroad. We were overwhelmed by the amount of information that we received in such a brief period. But we kept our minds focused on the last event on the agenda: seeing the Copa do Povo encampment. A day before our meeting the MTST carried out a series of organized protests that closed down major avenues and shopping centers in the West Zone of the city. According to the Brazilian daily Folha de S.Paulo the Sem-Teto movement mobilized 15,000 people. The journal reported that one of its leaders, Guilherme Boulos, threatened the current government that, “If there are no further investments in housing there will be no World Cup.” The journal also quoted Boulos as saying that the month of June would be transformed into a month of red, meaning a month full of protests organized by the Sem-Teto. Now, we were about to meet the group that paralyzed a sector of the city.

MTST ENCAMPMENT BESIDE ITAQUERÃO STADIUM

When the first ball rolls on June 12th to signal the start of the World Cup featuring a match between Brazil and Croatia an estimated 65,000 people will have a first class viewing to one of the most anticipated games ever. If they travel 3km from the stadium they will also have first row viewing of one of the biggest urban occupation camps in Sao Paulo.

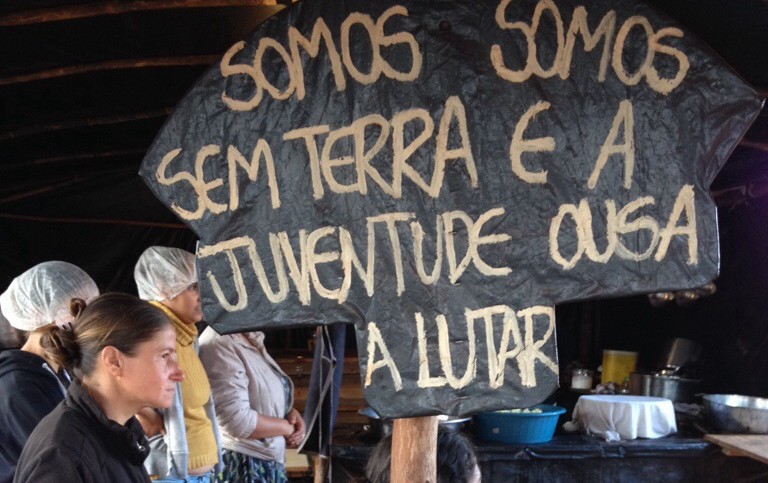

On May 2nd, hundreds of families from the MTST occupied land that was abandoned for years in the neighbourhood of Itaquera, and whose owner only paid R$57 ($28.5 CAD) on taxes last year on his entire land holdings estimated at R$47 billion ($23.5 billion CAD). Since then 5,000 have encamped in the area–that’s an estimated 20,000 people living in temporary tents made from bamboo and tarp. They argue that if the government has money for the World Cup they should also have money for a People’s Cup (Copa do Povo). Brazil has spent an estimated R$30Billion ($15Billion CAD) on the World Cup. According to Folha de S.Paulo that equates to only one month’s costs for education or 9% of the government’s total spending on education per year. But the people in the MTST camp argue that’s money that could have gone to needed social reform that didn’t. The people of the MTST camp continually reiterate that they are not against the World Cup, rather they are against how the money has been spent.

It’s two days before the World Cup starts and construction still continues on the stadiums of Porto Alegre and Sao Paulo. According to one source the series of works that the Brazilian government planned to have ready to host the World Cup should be delivered only throughout the second half of 2017, in other words three years after the end of the event. These unfinished projects include stadiums, airports, ports and urban mobility plans. MTST members criticized things like the building of the stadium in Manaus, an area so remote that the materials had to be shipped from France through the Amazon on ferry. They argue that the money spent on building a stadium that will only be used for four games and that will not be filled by the home team is ludicrous.

For these reasons the encampment has demanded the government to refocus its attention on urban issues like housing. According to the MTST officially there are 30 million people who don’t have proper housing in Brazil. In Sao Paulo there are 800 thousand to 1 million people without homes. The MTST’s slogan is for housing but they say their plans go beyond this. They consider people “without a roof” to be those who are spending 30% on rent, live in parent’s homes or dangerous situations like living on a hill. The MTST’s decision to occupy the area was a strategic decision to bring maximum pressure on the Brazilian government at a time when it’s most vulnerable. The government is facing presidential elections in October which further weakens its bargaining power. According to the Financial Times, “The combination of the two events is spurring on every form of activist group, from the homeless to unions. The government can do little but either meet their demands or try to stall them.”

THE MTST RECEIVES ITS DEMANDS, 17 YEARS OF URBAN REFORM

On June 9th the MTST announced that it had reached a deal with the federal government on three key issues. First, a project will be made for the construction of about 2,000 dwellings in the occupation of Copa do Povo land to meet the demand of MTST. The development will comprise federal funds, with supplementary subsidy from the state government and city of Sao Paulo. Second, the an Interministerial Commission will be established by the federal government for the prevention of forced evictions in the country, aiming to avoid conflicts and police violence. And lastly, measures will be created that strengthen the direct management of projects and the best quality and location of housing along with an amendment Ordinance, strengthening the care of families with excessive rent burdens of the program. This victory for the MTST comes at the heels of its 17 year anniversary.

The MTST was born in 1996 when the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem-Terra (MST) had a large national march and noticed the need for an urban movement while passing the city of Campinas. The MTST was initially organized in the city of Campinas, three hours northwest of Sao Paulo. In the initial stages the MST ran the movement but in 2003 the MTST became autonomous. Because of their shared roots the MTST and MST activists consider each other brothers and sisters in the same cause. . From 1996-2003 the movement slowly moved to the suburbs of Sao Paulo but at each occupation the movement failed to maintain its organization. It felt like it was starting over again at each time it mobilized. After 2003 the movement was able to reorganize and create a firm structure modeled after the structure of the MST. In 2005 they occupied land owned by Volkswagen Corporation in an occupation called Chico Mendes after a well known environmental activist and main founders of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT–the party currently in power.

From 2005-2010 the MTST began urban occupations in Campinas and the suburbs of Sao Paulo. In 2010 they expanded to the federal capital of Brasilia and now are present in eight states. They estimate a total membership of 900,000 people. A significant sum considering it took the MST 30 years to reach 1.5 million members. In 2013 the movement organized its first occupation in the city of Sao Paulo and in one year they orchestrated six occupations, one of which called New Palestine is made up of approximately 32,000 people. The organization is growing rapidly and is one of the few that works with the city’s homeless in Sao Paulo. The biggest issue the movement faces is security considering the urban context. However, each encampment is structured in the same form as MST encampments and they organizned round the clock surveillance at each occupation to lessen the danger of living in an urban camp. In Copa do Povo as with our last encampment in Itapeva the camp has large support from the neighbourhoods dwellers and recieve daily donations of food and clothing. The movement has received large support from a broad national base because their supporters believe the cause is just.

When housing is awarded, families are selected based on their involvement in the movement just like the MST. The housing varies according to the setting; in smaller cities they are separate houses built by the federal government and sold at cost prices or apartments in large cities like Sao Paulo. The government sells a dwelling to each family with a 10 year stipend of R$110 ($55 CAD). After 10 years families receive the title to the home. At each location a school and health clinic is built to ensure the needs of the families are met. Currently some 600 families in the MTST will be the firsts to receive their new dwellings after 17 years of activism. The federal works have been built to code and have faced little problems during the financing and construction phases. Each family that receives a home is expected to stay in the movement to help others in their own struggle. An act that will be tested once the families settled into their new homes later this year. For the MTST these arrangements with the governemnt are large victories but relatively small in an effort to reform an even bigger social problem of years of exclusion toward the poor and roofless.