Alexandra Kollontai Settlement

Named after a Soviet female writer the settlement of Alexandra Kollontai (Alexandra Koluntai) has existed for 14 years. Prior to becoming a permanent settlement the 80 families who now call the area home were encamped for five years. In 2000 when the state expropriated the land from a large landowner who was heavily in debt and had failed to pay his taxes for years, the 150 people who were encamped in the area were facing their 12th eviction. The day of the court ruling (to decide whether the state would award the land to the landless MST families) the encampment was circled by 400 heavily armed military police officers, officers on horses, and helicopters above. At the same time representatives of the MST and the fezandero (large landowner) were in judicial dialogue in Brazil’s capital city of Brasilia and in Sao Paulo. As the military police approached the encampment to force the families out, the camp received a call telling them that the judge overseeing the case had awarded the families the land citing the owner’s financial situation and his practice of monoculture planting. Emotions were overwhelming in the camp and tears flowed freely. The officer in charge approached the camp and congratulated the camp on receiving the land.

“He apologized to us for treating us like they had and told us he and his men were just doing their job,” said Emis the local farmer showing us his plot of land in Alexandra Kollontai settlement. “There were no hard feelings.” Shortly after receiving their land the families began the process of dividing it among the 80 families and building their permanent homes. Emis recounts how at first the encampment had as many as 150 families, but many gave up the struggle (luta) and only 80 remained to receive land. The euphoria of getting land quickly subsided as families faced the reality of Agrarian Reform. “80 percent of the families in the settlement are in debt,” Emis tells us. He explains that when families are awarded land the state is responsible for providing the technical assistance, infrastructure and proper irrigation system for families to begin their operations but in the early days this was hard to come by–if it ever came. “When I got my land the government gave me R$5,000 ($2,500 CAD) to build my house.”

Our translator and professor Dan exclaims, “that’s a misery!”

Emis continues, “today people receive R$25,000 ($12,500 CAD).” At first glance this may seem like a lot but it becomes miniscule when taking into account that a farmer must build a home, buy seeds and seedlings ranging from $0.75-$4 CAD. Considering that each farmer must plant between 200-400 seeds and seedlings, of 12-20 crops, build a decent house, and have money for necessary goods they cannot grow, the money runs out quickly. “Because the government didn’t provide [the infrastructure, technical assistance and irrigation system] many of the farmers took out loans in order to pay for these things,” Emis tell us. He says that because many of the people in the settlement had never worked the land before (himself included) their first crops failed to produce the needed profit to pay back their debt.

Working the land for the past 14 years has made up for this says Emis. He explains how about 10 percent of the families are now self sufficient and debt free only needing to go to the city for few basic needs like salt, sugar and some meet. They are also negotiating a deal with the state to have 80 percent of the settlement’s debt with the banks absolved. He himself has become so well versed in the science of agriforest methods that he now travels across Brazil lecturing on the benefits of biodiversity in crop planting and of reforestation of the land using agriecology principles. He has become the biggest producer of organic bananas in the region producing 1/2 a ton every three to four weeks using zero pesticides and fertilizers and sells his produce to wealthy Brazilians in large cities across the state. He hopes to increase his production to 1.5 tons so that he can begin making his own Cachaça (Kaxassa), a local liquor made from fruits or sugar cane. In order to make up for the challenges of a weakened soil he introduces into his gardens various plants, trees and vines that add phosphorous, potassium and nitrogen into the soils to feed the surrounding crops of fruit trees, vegetables, medicinal herbs, and legumes. Even when his crops are completely destroyed due to fires caused by the dry conditions of the region he explains that the land recuperates faster than the land of large monoculture projects.

Two years ago he lost his entire banana crop to accidental and intentional burnings yet noted that within a few months the banana saplings began growing and within a year had produced another full crop. This form of diversification, nourishing of the land and continual development in the knowledge of experimental agronomy is at the root of what the MST wants to promote among its members. Even though agriforesting is known and recognized among small scale farmers as an optimal system of growing crops the labour intensity it requires as wells as the knowledge that a person must possess in order to effectively grow complimentary crops is too much for most farmers. In the Alexandra Kollontai settlement only 16 families are using Emis’ method of agriforesting, most are still using conventional methods to grow single crops. Because most farmers are in debt they are still heavily dependent on the state for subsidies to keep their operations going. Large corporations involved in ethanol and biofuels production are also heavily dependent on state subsidies. According to our professor Dan and his assistant Melinda, last year agribusinesses received R$110 billion ($550 billion CAD) in subsidies whereas small scale farmers received R$10 million ($5 million CAD). The large inequality of state support can be explained in terms of economics. Brazil’s economy is heavily dependent on biofuels and ethanol production and thus invests heavily in the industry. Like Alberta’s Tar Sands the government in Brazil promotes this “natural resource” as a green alternative in an energy pinched world.

Struggling for a dream–the Fazenda Martinopolis encampment

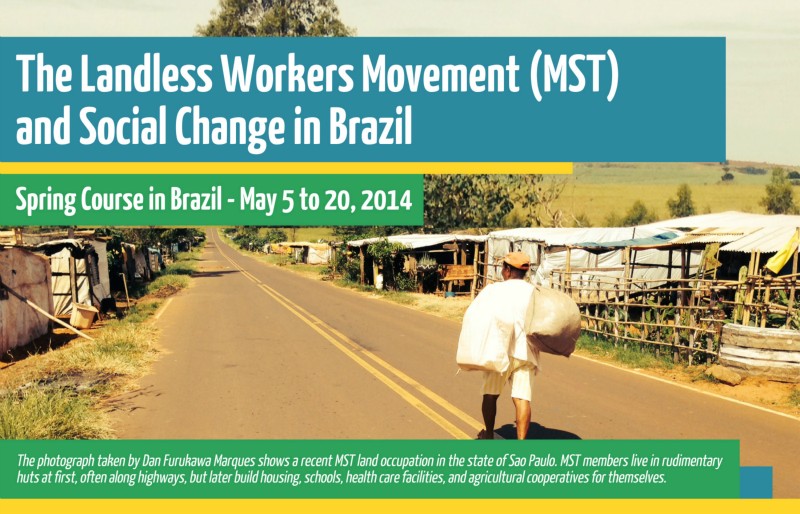

On the opposite side of the highway dividing Alexandra Kollontai settlement and a few kilometres from Emis’ plot sits a plot of land covered in makeshift homes with blue and black tarp roofs. The neatly organized cluster of homes is an MST emergency encampment made up of 450 families and sits next to a large fazenda (large private land in the hands of one owner) that is heavily in debt. The families who have occupied the land for the last five years are fighting to have the land of Fazenda Martinopolis expropriated and divided among the families for subsistence farming. They are made up of city dwellers from the adjacent city and from the city of Riberao Preto. Some work as construction workers, elevator operators and as well as many other city jobs and are primarily from the favelas (city shanty towns).

“Everyone’s dream in the favelas is to have their own home and a little piece of land,” says a woman who was recruited to the encampment by her brother. “God willing we’ll have some land.” She tells our group of five how in the city she had fallen into a state of depression and decided to visit her brother in the encampment. While here she learned of the MST’s encampment rules: no prostitution, no stealing, no hitting your spouse, no heavy drinking, etc. Because the camp provided a better sense of security and enforcement of the rules (first time offender is called out, second time offenders may be expelled) she quickly became convinced that this was the best choice for her family. She and her husband along with their two children moved to encampment and began learning about the struggle for land.

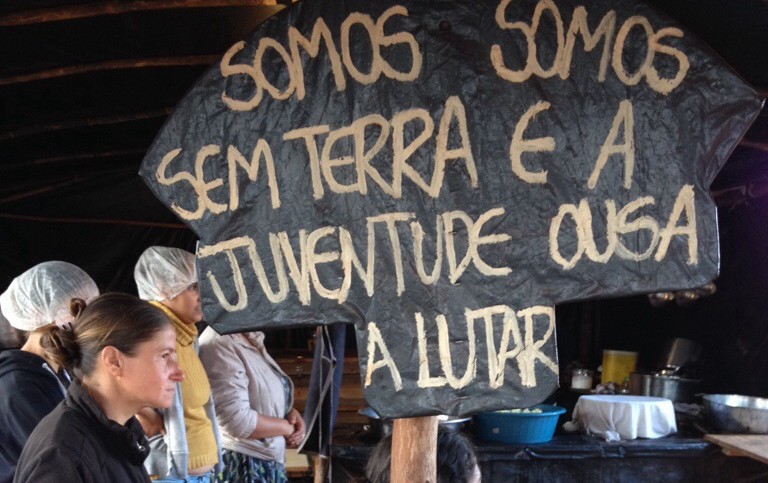

Prior to coming she had little to no exposure to the MST and the various Agrarian Reform movements in Brazil. Orlando, a local MST activist from Sao Paulo accompanying our group explains to me how in Brazil the MST is painted in two lights. “The media either paints [the MST] as a group of people wanting to live a dream in a Utopia, or they say they are thieves, vandals and even terrorist,” he says. He tells me that Globo, Brazil’s largest television chain is notorious for this. Among the various encamped families many had very little to no prior exposure to the MST. Membership in the organization sits around 1.5 million members, though that figure fluctuates up or down depending on the source. Considering that Brazil’s population is about 200 million the MST makes up only 0.0075 percent of the total population. While the MST is the most significant group calling for Agrarian Reform in Brazil it’s no wonder why Agrarian Reform is not a government priority and its advocates are still perceived by many as a small group of “vandals.”

Another man wearing aviator glasses beside a makeshift house down the street tells our group of the reality MST occupiers face when they come to live in the camps. “When I first came here I thought I was going to struggle to get land,” he says. “After being here I learned I was going to struggle for the dream of one one day getting land.” He tells our group that when people come to the MST encampments they are faced with the reality that they may spend years in precarious conditions with very little comfort. They will face discrimination, constant evections, threats and the use of force by military police and hired gunmen. The people in the emergency encampment of Alexandra Kollontai have high hopes that land will be awarded to them. They hope they can one day reclaim the land their parents once worked on and build a settlement like that of Maria Lagos. As the man in the aviators tells us, “for me it’s like coming back to my roots.”