The course assistant Melinda and I sit inside a 61-seat bus on its way back to Sao Paulo. The participants of the Latin American Leader’s Formation course are going to the city to join a national march organized by the MST. The group chants the MST hymn and rewrites the lyrics to a popular Brazilian song called “Lepo, Lepo.” The song, originally about a broke man who wonders whether a particular girl will stay with him once she realizes he no longer has money, has become popular among Brazilian youth. Rather than keeping the sexually provocative lyrics the new words speak of social reform, support for feminist movements and urban poor.

“This is the happiest group I’ve seen,” says Melinda. “Usually everyone is…tired before a march.”

The march began two days ago with the majority of the 1,500 participants coming from outside of Sao Paulo city and making their way towards a large meeting spot. The group made a 26km march the first day followed by an 20km march into Sao Paulo. The small group of just over sixty coming from the school will be minuscule addition to the march. The target is a large multinational corporation, which according to the participants, has stained its hands with the blood of poor rural workers. The plans are well known to the group but at the moment they will not be told where, or who the target is until they arrive at the city. This veil of secrecy is meant to protect the marchers from police or private security repression. By keeping the target secret the police and private security will have little time to form and harm the protestors.

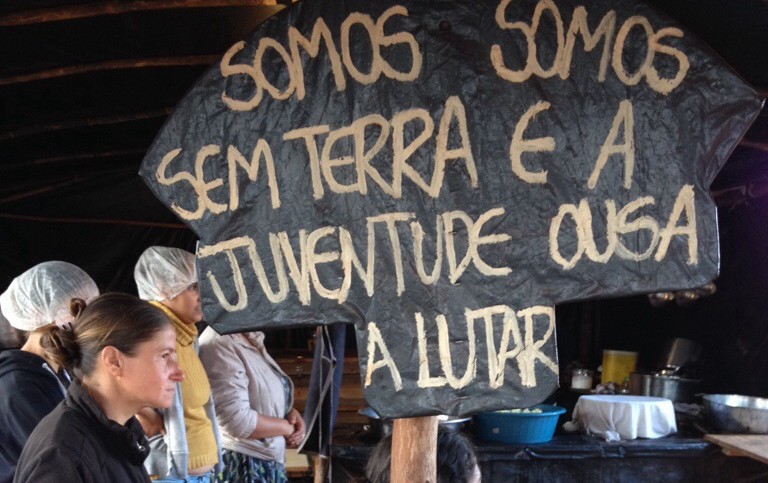

Marches, chants and civil disobedience are all part of the leftist culture. The use of military terms like militant, brigade, and cells form part of the lexicon of socialist or revolutionary rhetoric. But, the members of the various leftist organizations are not armed. They are also not a military organization. Their only weapons are the banners they prepared and the various flags from their respective countries and social movement groups, which they carry proudly. The MST members who have already been marching toward Sao Paulo will march in solidarity with other urban reform groups based in Sao Paulo.

For us Canadians observing the events will be of great interest. This large manifestation is an act of solidarity for rural land reform and to support urban groups focused on urban housing issues. It carries the name of Luiz Beltrame, one of the MST’s oldest militant, at 106 years old he is being honoured for his many years in the Agrarian Reform movement. The group seeks to demand that the government begin prioritizing on the Brazilian people rather than giving preferential treatment to international corporations, agrobusiness, as well as the World Cup.

Understanding the March

“The people demand not just agrarian and rural reform but a prioritization of the government on the Brazilian people and not on American and foreign companies,” a participant tells me. She explains that the large crowd is marching to demand the government to refocus on issues such as rural and urban housing, healthcare and education.

“We’re not against the World Cup,” she says, “but think about it, who’s going to pay for the cost of hosting it? The working class, that’s who.” She explains how she believes the price of food, healthcare and gasoline will eventually increase once the event is over so as to offset the high price of hosting the competition in Brazil. She argues that the ones who will be primarily affected by this increase in the price of goods will be the poor. The crowd is composed of landless urban and rural MST members.

Tonight the large gathering of MST members rests under the outdoor gymnasium of a local school and enjoy a cultural night before the long march tomorrow. They eat dinner prepared by MST cooks: a plate of pinto beans, rice, cassava mixed with pork, cucumbers and two tangerines per person. The logistics of feeding such a large mass is incredible. The food is free of pesticides and not genetically modified. It is a testament to the agroecological methods currently being implemented in various MST settlements, not to mention incredibly tasty and very filling.

The cultural night is composed of an open mike set up where anyone is welcomed to perform a musical piece, a poetic declaration or any informal declaration they wish to share with the crowd. The crowd sings along to popular socialist songs to the beat of Forró (a Brazilian ballroom dance) and Sertanejo (a rustic type of country music). A young man sheepishly steps up to the mike and tells the crowd he will perform a different kind if song. The guitar player provides a consistent urban sounding beat and the young man begins a fast-paced rap about following your dreams and fighting for land. The most curious is a man who performs the MST’s hymn using a bull’s horn. But the performer who receives the loudest response is a little girl who performs a popular chant, after which the crowd responds with loud whistles and claps.

The night’s festivities are a welcomed distraction for the crowd who has marched for two days and has made the 46km trajectory to reach Sao Paulo. While the environment inside the school grounds is festive and light-hearted the mood outside is not. The large group has camped inside a large middle-class neighbourhood who’s inhabitants do not all support the MST or its ideology. The participants are warned about going outside alone and are told not to wear anything identifying them with the movement. They are told of the cold welcoming the MST received from the neighbourhood and of reporters wishing to jump the school’s fence to infiltrate the camp. They are warned about the possibility of possible repression from unsympathetic neighbours.

The festivities end at 10pm but the socializing goes late into the night. Fed, entertained and well accommodated the crowd prepares for bed. Tomorrow they will complete the final leg of their three-day march and with it another “fight” for Agrarian and Social Reform in Brazil.