The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly—A look at Brazil’s Agrarian Reform Movement

Vem, lutemos, punho erguido (Come, let us fight, with raised fist)

Nossa força nos leva a edificar (Our strength leads us to build)

Nossa Pátria livre e forte (Our Motherland free and strong)

Construida pelo poder popular (Built by the power of the people)

—Chorus of the MST National Anthem

After spending close to a month among members of O Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra (MST) I formed a fair and balanced opinion of the strengths and weaknesses of the movement. Though my observations need to be classified as a first-time observant and not as an expert on the matter my journalism training will allow me to be as objective as possible and provide a balanced essay.

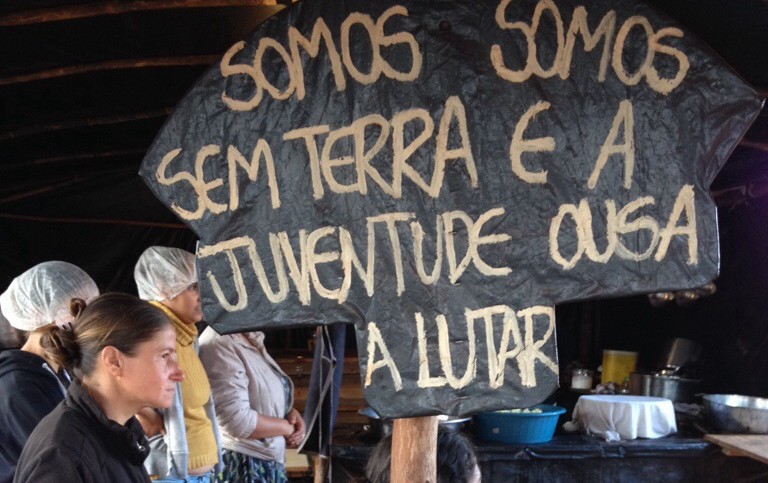

When I reviewed the various experiences our group had the privilege of living such as studying socialist economic models of production in the Florestan Fernandes National School (ENFF), observing an MST led march, getting acquainted with alternative food production models, experiencing life in the various settlements and encampments in the state of Sao Paulo as well as seeing one of the largest urban occupations in the city of Sao Paulo I acknowledge that the biggest strength of the MST is its capacity to organize.

This grassroots movements is truly a grassroots movement. There is no hierarchical order with a president and sub-presidents underneath to mobilize the masses but rather the leadership that is made up of 20,000 delegates from the various respective encampments and settlements. Individuals serve in their respective roles voluntarily and in some cases for indefinite periods of time. They do not choose their assignment but are selected based on active participation. The movement is inclusive rather than exclusive.

Because of this a key strength within the MST is the inclusion of women. From the beginning women have played a crucial role in the formation of the movement. Their defiant role during the first land occupations in 1979 which led to the formation of the movement proved crucial to the survival of the first two camps as well as set the pattern for the active participation of women in all aspects of the national decision making. The “Frente de Massa” or Front of the Masses refers to the group of individuals at the front of each march who act as a barrier between repressive forces and protestors. The women of the 1979 occupations played a crucial role in establishing this effective technique to confront the government and other oppressive forces. Because women were the catalyst for other movements in the areas neighbouring the two initial occupations in Rio Grande do Sul and because they represented a new tactful weapon against state and local violence the MST began to deliberately recruit women and to set up special committees and organizational structures for them within each movement. An illustration of this is given by Lynn Stephen when he cites an MST document from 1986 which reads: ‘‘We will fight for a just and equal society . . . reinforcing the fight for land, including the participation of all rural workers, and stimulating the participation of women at all levels’’

But while this ideal has been pursued women’s participation is not on par with the men. Women still count as a growing minority in the various administrative and national roles.

Women have also been influential in another key area of the MST: the promotion of education. Since the first encampments it was women who were increasingly aware of the need for an educational arm to the social activism the children and illiterate adults of the camp were participating in. They were the catalyst for the formation of state funded schools which focused on education based on rural needs and with Agrarian Reform values as part of the pedagogy. They helped to create an alternative way of learning based on practical rural setting which allowed children to learn things like growing organic gardens in school and learning crop cycles as well as new technology and programs aimed at helping them pass the national university entrance exam. The MST ‘s own ENFF school is based on this alternative method of teaching as is the result of the dreams of many.

The MST’s focus on education has allowed it to create formal links with various state universities in order to create a government recognized degree in Agrarian Reform and agriforesting aimed at the youth of MST settlers and those seeking alternative means of safe food production.

But the MST is now without weaknesses. One of which is the the exodus of youth from the rural areas to work in the city. While we were in Riberao Preto one of our guide told us how her children had each decided to take jobs in the city rather than work the land. When I asked her daughter why she had chosen to take a job in the city and commute the hour to work at a Pizzaria she said, “we don’t make enough money here. I have to work in the city to make money.” Melinda, one of the assistants is currently doing her PHD thesis on the issues and difficulties the MST youth face while living in the interior and why many of them are moving into the cities. Her research focuses particularly on youth in the northeast of the country. Our guide confided in us that she not only works her land to provide for the association she belongs to but also has a weekend job in the city to bring in extra income since her farming does not provide the required funds for her family’s needs.

This economic factor of unresolved debt affecting the future longevity of the movement was uniform across the settlements we visited in the state of Sao Paulo and according to the authors of To Inherit the Earth the majority of MST settlements are in debt because they have not been able to pay back their initial loans. This is partly due to the government’s lack of funding compared to the funding the agribusinesses receive. It’s also partly due to the fact the initial MST settlers were not farmers but city dwellers and their initial crops failed to produce the require income to pay back the debt. Successive crops have failed to make up for the cost of production even when they return to conventional single-crop production.

Another factor affecting the movement is its heavy socialist rhetoric and its alienation of the working class in the city. Socialism is a social and economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and co-operative management of the economy, as well as a political theory and movement that aims at the establishment of such a system. In the case of the MST this social ownership may refer to cooperative enterprises, common ownership, state ownership, citizen ownership of equity, associations or any combination of these. The MST adamantly opposes the capitalist system. Private ownership of land and the centralization of wealth by the few is something it seeks to abolish in hopes of establishing a more fair and egalitarian society. Yet some of the people I spoke with from Sao Paulo to Porto Alegre all the way to the capital city of Brasilia did not wish to associate with the socialist model. In their eyes the MST’s goals were admirable but unattainable.

Those I spoke with were store owners, students, businessmen, a manager at a major Brazilian bank, real estate agents and government employee. They all recognized that while the few elites in Brazil are continually getting richer the poor under the Lula and Dilma governments are beginning to step out of poverty. They acknowledge that while the new socialist programs inspired by groups such as the MST have been good for large group of underprivileged Brazilians those who have been left to carry the financial burden have been the growing middle class. While on the one hand capitalism is making the rich richer and socialism is providing a door for the poor out of misery, the middle class has access to neither of these. According to the World Bank Brazil’s middle class makes up 1/3 of the country’s total population. This one third is responsible for financing the government’s policies through its taxes.

As a special report news agency service Reuters reported on July 3, 2013:

“The very notion of middle class in Brazil is quite different from the standards of North America and Western Europe.

No tree-lined suburbs and Volvos for the newly empowered masses here.

Instead, the term is used broadly to include almost anyone able to pay rent, put food on the table and perhaps pay a monthly installment on the refrigerator, microwave or television that Brazil’s government often touts as a sign of their emergence. The so-called “Classe C,” the bottom rung of Brazil’s middle class, earns as little as 1,730 reais a month, about $790, and, unlike the much-smaller upper middle class, relies largely on public transportation, health services and schools.”

It is this middle class that took to the streets last summer to protest against the rising bus fair of a mere 20 cents. While that may seem trivial consider that a bus far in Sao Paulo is 3 reais per trip. The metro is a seperate 3 reais and if one is travelling on select lines the fare increases to 3.50 or more depending on the number of cross-city connections. Multiply this times two trips per day for a month and 20 cents begins to add up. So while socialism has offered various social programs to help Brazil’s poor the middle class has been the ones to finance it yet are not able to access these same programs because of their social standing.

With all of this in mind the fact that the MST is made up of only 1.5 million rural members in comparison to the almost 168 million urban Brazilians it is easy to recognize why Agrarian Reform under the MST’s desired goals have proven difficult over the last 30 years.

The Canadian Perspective—Lessons for Canada

Canada does not have a problem of land distribution or social reform. Well, not like Brazil. The majority of our land is relatively purchasable. And because Canada’s population is only 33 million people we have land to spare as well as the ability to pay for our social programs. In terms of Land Reform we do not compare nor relate to Brazil’s dilemma. But there are a few things we do relate on: our heavy reliance on pesticides for food and non-food production and the increasing deforestation of our land for natural resource exploration.

As stated in my last article Brazil has the most amount of arable land yet it is being deforested to make way for monocultures such as sugar cane, eucalyptus, soya and corn primarily meant for export to China, US, and Europe to be used as feedstock or ethanol in the case of sugar cane. This practice erodes the soils, contaminates water ways and endangers people’s health and ruins important bio diverse ecosystems. In like fashion our boreal forest in northern Alberta is increasingly being cut down to extract bitumen, natural gas and coal. This increase of resource extraction since the 1947 when the Leduc No. 1 oil well was discovered has transformed northern Alberta’s landscape. While the Alberta Tar sands are an important resource for energy in in the region we must asses the claims made by a small few regarding both the environmental and health risks of such operations. We must learn learn what we can regarding this pristine area of the world and preserve as much of it as possible. We must learn to not commit the same mistakes as Brazil and poison our waterways.

In Brazil’s agricultural states mainly in the south and northeast landscape has been reduced to industrial production in some areas where forest (cerrado) used to cover the visage. That production is now slowing down or being abandoned because of lack of demand or eroded soils. The saltation of the earth caused by heavy pesticide use has forced some communities to abandon their homes and move else where as the production there has completed wasted the land. We must learn from our southern neighbours not to do the same with our land.