This article is part of a short series on the Brazilian Agrarian Reform movement known as the MST. It will be divided into two articles: the first will give a brief history and the context of the movement and the next will asses the strength and weaknesses of the MST as well as give a Canadian perspective for the movement.

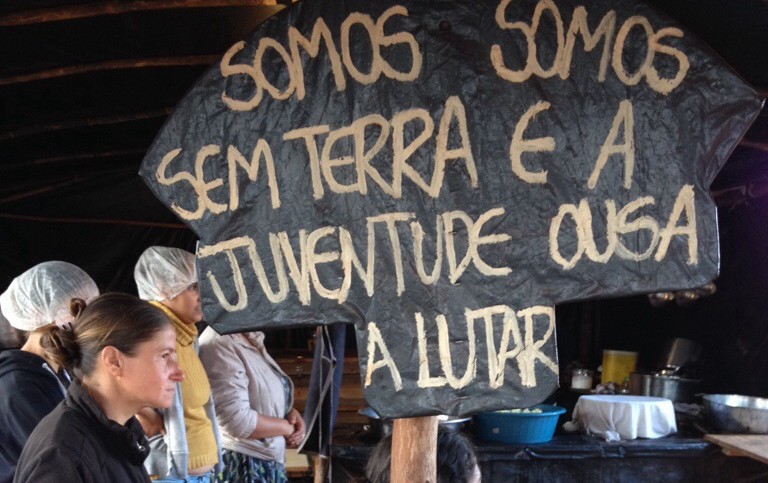

MST a luta é pra valer! MST a luta é pra valer!

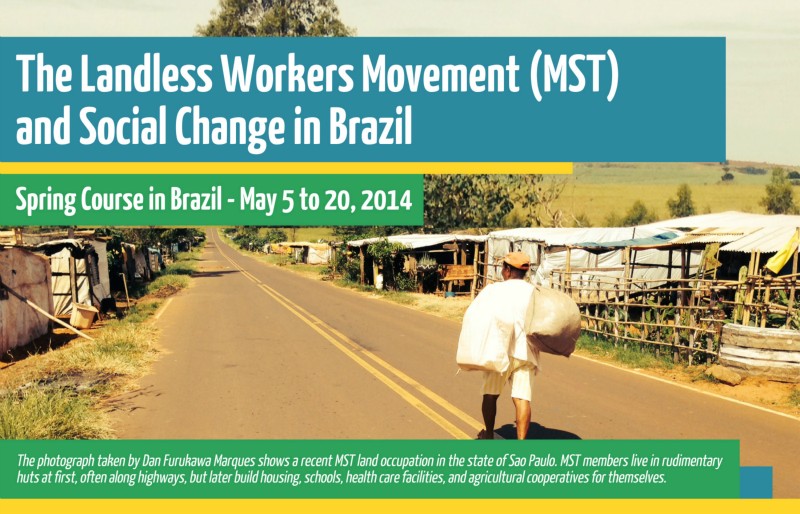

When I received an email on January 11, 2014 about a university spring course in Brazil I almost tossed it in the trash bin. I’m glad I didn’t. I sent an email to Dan Furukawa Marques, a PHD candidate at the University of Ottawa asking for further information. With this act I was about to embark on one of the most intensive interdisciplinary courses of my university experience.

Within a few hours of receiving my email Dan replied with all the necessary information for me to apply for the course. I instantly realized this was not going to be a regular spring course. I was required to answer seven questions regarding my involvement in NGO’s, volunteer organizations and activism. I was also told to be prepare for the various living environments we would experience—some of which not common to North American standards. My application became a three page written response form. After my application was assessed I had a 20 minute Skype interview with Dan. I was told I had been accepted into the program. I was also told that I was required to begin studying Portuguese and was required to read a list of books and articles on Brazil’s Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra (MST-Landless Workers Movement), submit a 12 pager paper based on the readings and prepare a 4 page summary presentation to be presented to the MST leadership and my class on the first day of the course. All of this was required to be done before the course began on May 6, 2014.

A Brief History of the MST

Prior to entering the course offered through Bishop’s University in Sherbrooke, Quebec, I had very little understanding of the various Social Movements in Brazil and had only heard of the MST from small readings in school. I was not aware of the polemic nature of the group and the political power it commanded. I was informed that the group had about 1.5 million “members” and was one of the most influential Social Movements in Brazil.

Brazil has the highest amount of arable land in the world yet very few people actually own it. Since colonization Portuguese officials have sought to resolve the problems of inequality and poor land use in Brazil to no avail. One principle of the law that was intended to curve this was the principle of “effective use”; the notion that if land was not being effectively used by an owner others could make a competing claim and acquire the title to the land for themselves. This principle of effective land use was so well known that wealthy landowners began manipulating the system so as to force small scale farmers off of their land. While it was evident that the law was being twisted, a version of it became nonetheless enshrined in the Brazilian constitution. The law stated that land in order to be claimed by an owner had to “serve its social function.”

Successive governments who recognized the contradiction posed by large landowners with uncultivated land and the large gap of inequality this created promised to use this law to expropriate land from the fazenderos (large land owners) and redistribute it to the working poor. But these promises were rarely fulfilled. According to Maurilio de Lima Galdino co-author of Collective Action and Radicalism in Brazil the origin of the MST can be traced back to the small land holders who lost their land because of the construction of hydroelectric dams, and in more general terms, to the agrarian modernization of Brazil between 1960 and 1980 that so drastically changed the working environment in the Brazilian countryside.

This “Green Revolution” left many in the countryside without lands to work and without a way to support themselves and their families. While the majority of them decided to move to the major cities creating the infamous favelas, or shanty towns, of Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo a small few decided to make a stand against large multinational corporations and fazenderos whose lands were not serving the social function as dictated by the constitution. These became known as the landless.

In 1979 as displaced settlers in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul were being driven out of indigenous land, discussions arose among the local clergy and sympathizers of the landless regarding land claims from large landholders and corporations who were not putting the land to good use. The local clergy instructed the people to occupy two possible sites where the government had declared the land had not been used properly by a corporation and where expropriation was going to happen later that year. With the help of the clergy and with enormous public support for the idea the landless from the region organized themselves to sit in on the land and to demand the government to redistribute it among the families. When the government sent in the army to remove the occupiers the women in the company chose a dramatic yet effective way of disarming it: they chose to stay with their men. As one of the main clergy who helped organized the occupiers recalls, the women said “If you’re going to beat our men, you will have to do it by coming over us first.”

This critical step of stepping up for their men and deciding to stick together as a family proved crucial as the army hesitated to beat the women and children and found it could not break the lines formed by the settlers. The women’s consistent presence and their active participation in the quest for land reform proved an effective tactic in forcing the government to comply in this and subsequent land redistribution claims. The success of this occupation gave momentum to the next phase in the creation of the MST: an occupation of land that was claimed by private landowners but being disputed in court.

In December 1979 another occupation took take place in an intersection of the highway between Ronda Alta and Passo Fundo. This would mark the beginnings of the MST as a large solidarity movement which would later pave the way for a larger national movement on agrarian reform in Brazil. Popularly known as the Encruzilhada Natalino (Natalino Intersection) the occupiers faced off against military police (a special force controlled by the state government) and the land owner’s hired guns. As the months turned into years of occupation the movement began to receive more national coverage resulting in growing popular support for the occupiers. The movement began setting off other occupations in the region and began amassing the image of a national movement on land reform.

Understanding the Sem Terra: Occupying vs Invading

As Tanya Reimer explains, the landless workers in Brazil are known as the Sem Terra. There is no collective noun for the English word of “peasant” in Portuguese. Sem Terra literally means “without land.” The term originated from journalists covering the highly politicized confrontation at Encruzilhada Natalino. Over time the Sem Terra concept has come to encompass a large group of people: small farmers, tenant farmers, sharecroppers, day workers, seasonal labourers, peasant farmers, and squatters. Despite the differences between these groups of people they all share an experience of poverty and exploitation. More specifically, they share an “exclusion from the wealth they had helped to generate.”

She further adds that the Sem Terra concept unites the excluded in their struggle for social, economic and political inclusion. The Sem Terra are located in the agricultural states of Brazil, predominantly in the South and Northeast. Reimer explains that the composition of the Sem Terra varies in each state. In the Northeast, farmers are generally mestizos (mixed race), while southern farmers are generally European migrants. According to Reimer the Sem Terra make up about 30 million of Brazil’s total population of 200 million.

The MST has managed to organize 1.5 million of the Sem Terra under the banner of Agrarian Reform and socialist ideology.

“The problem with the Sem Terra is that the media always shows them invading some poor persons house or farm. They break and steal stuff all the time,” Gisele Miranda a friend from Campinas in Sao Paulo state tells me as we have dinner. “That’s wrong, isn’t it?”

I explain to her that the MST does not work in such unorganized and reckless manner, but there are cases when occupations are done under the banner of the MST by reckless individuals trying to get exposure on the media—and the media eats this up. I also explain to her that there is a difference between “invading” and “occupying” and that the difference is primarily a matter of ideology and semantics (meaning of the each word).

When the MST occupies a large farm it does so under the following guidelines:

- The property’s land title has been proven to be fake

- There is clear evidence that the land owner has acquired the land illegally through intimidation, theft, or other unfair practices

- The owner is heavily in debt and is in talks with the government to have the land expropriated

- The property has not been producing anything for years

- The land owner practices monoculture

When one or more of these have been proven the MST begins legal action against the landowner under the constitutional clause that the land is not meeting its social function. At the same time a team is organized to in occupy the land to speed the process and allow families direct access to the land. All of this is legal under the Brazilian constitution. Yet, few people understand this social clause primarily because they’re usually only shown images of the people entering a farm and are not given the context.

While in Sao Paulo I personally saw two reports like these. One was an urban occupation on the east zone of Sao Paulo in a protected natural reserve while the other was a rural one in the interior of the state. On both of these the people were shown entering a farm cheering as they cut down a fence. On the rural one a group of people dressed in all red are shown breaking windows and doors protesting the rape of a young girl by the land owner. Images like these are imprinted into the Brazilian audience’s mind with little context beside acknowledging the difficulty of Agrarian Reform in Brazil. During these reports both occupations were described as being “invasions” of private property. Most times the MST is portrayed as a violent group who cares little about the individual rights and the private property of others.

A quick search under the keyword “MST” on Globo TV’s site yields various videos about the movement. The first is titled “MST protestors break a car after driver runs over a child in Rio Grande do Norte.” Videos often portraying violent confrontations between protestors and the police are constantly being shown on the primetime news networks.

Agrarian Reform under Socialist terms

As journalists Leandro Arnoch explains in his book Politically incorrect guide of Latin America “the recipe to being a good Latin American includes…condemning capitalism. The Latin American [including socialist Brazilian] who honours the name believes that communism was a good idea—just badly implemented. And, if he doesn’t fight to implement that failed system here, at least he’ll defend models that are more “socialist”, build “solidarity”, are “just” and “community” oriented.”

In the case of the MST their ideology is firmly based on a Marxist framework and are openly opponents to capitalism’s centralization of wealth and land. They draw inspiration from critical thinkers such as Marx and Engels, Antonio Gramsci, and popularly support such iconic communist and socialist leaders as Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Hugo Chavez as well as Brazilian educator Florestan Fernandes. They have dedicated various MST run schools to promoting this ideology among their members. One of them is the Florestan Fernandes National School in Sao Paulo. They are naturally critical of political parties and their promises and are not associated to any one party, though many openly support the Dilma government because of the ideological similarities between her party and the movement. From the beginning of the movement they have decided to be autonomous from any religious or political organization and not only seek to decentralize land control in Brazil but also to change the way the country uses the land, how its food is produced and how its wealth is distributed.

Brazil is one of the richest South American countries. It also has one of the highest levels of uneven distribution of wealth. By amassing popular support the MST has inspired, supported as well as created other social movements addressing the country’s various ills. It has done so under the banner of socialism: decentralized wealth and land, community based farming, support for social programs such as alphabetization of children and adults using state funds, opposing foreign control of natural resources such as water, electricity, oil and precious minerals and politicization of the masses. For only accounting to 0.0075% of the total population the MST has proven a rather effective political force.