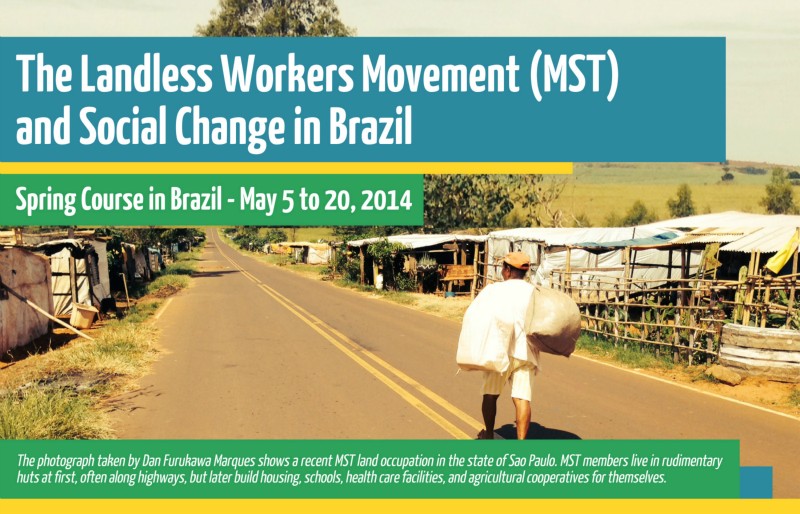

The morning breaks and the shadows begin to flee. All around me there is an orchestra of sound. Humming birds, crickets, hens and various birds chirp, tweet and call out for each other. Today our group is in the Center of the 6 Itapeva Settlements, a place bordering the state of Paraná seven hours south of Ribeirão Preto. According to our professor Dan Furukawa Marques the settlement is the best example in the state of Sao Paulo of a working cooperative. The settlement boasts an agriecology school, a refinery where they make their own Cachaça (Caxassa) called “Cachaça Socialista” (Socialist Cachasa) and a school for children 0-5 years old.

Last night during dinner Dan told me how important the rural production of food is for Brazil. About 80 percent “of the food Brazilians eat comes from small scale farmers,” he said. “Not everything is produced by the MST settlements, a lot of it comes from small scale farmers who have nothing to do with the MST” he noted. A common phrase among MST famers is “If the countryside doesn’t plant the city doesn’t eat.” I ask him if the small scale farmers producing Brazil’s foods practice agriecology like MST farmers or if they use conventional methods. He responds by saying all of them use conventional methods.

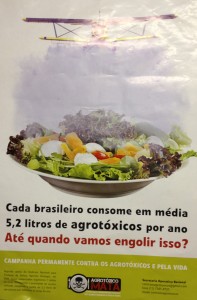

A commonly known statistic among MST and organic growers is that on average every Brazilian eats about 5 litres of pesticides a year because of the way their food is grown. One fact that is often reported and known by many Brazilians is that Brazil is the number one importer of pesticides in the world. According to a report by the firm Worldwide Crop Chemicals, Brazil was the second fastest growing market in the world between 2004 and 2009. In 2008 it became the world’s top consumer of agriculture pesticides (ahead of the US). Brazil is one of the world’s most productive agricultural regions, and its pesticide market is known for having high sales volumes ($4.5 billion CAD in 2005 at the distributor level); high sales margins (one of the highest in the world); and for having difficult market access caused by very complex regulatory legislation, elevated costs, and lots of paperwork. Dan tells me that pesticides that have been banned in the US and Canada are produced and still heavily used here. Brazilians who can afford to pay for pesticide free foods will usually pay the extra price to avoid the adverse effects of consuming “agritoxics.” The MST movement believes that a different system of production must be adopted if all Brazilians are to live longer healthier lives.

MST ENCAMPMENT IN FORESTING GROUNDS

A mural at the Itapeva settlement’s diner has the slogan “Health starts at the mouth.” It shows a young girl surrounded by fruits and vegetables. During our stay with the MST’s various encampments and settlements we have been treated to pesticide and industrial fertilizer-free meals. Lettuce, carrots, beats, onions, okra, beans and rice have been a common addition to portions of beef, chicken and fish. Fruits like papaya, mango, apples, acerola (a cherry found in the amazon that contains 10 times the vitaminc C content of one orange), bananas, and oranges have been common treats. I can say that while I have always had a healthy and diversified diet I have never enjoyed lettuce the way I do now. While I used to consider it rabbit food I now usually have two or three helpings at each meal. I’m not alone in my love of this vegetable. Most of my group feels the same way. But healthy food production is one of the many reforms the MST calls for. As with other areas of the city the MST wants more involvement of youth in the rural sector and calls for their social reform of its members so as to become different and more productive members of society.

About 15 min away from the “sede” (headquarters, center) of the six settlements in Itapeva is a new settlement of one month. The settlement is positioned in a strategic point at the center of a reforesting project on state owned land that is being rented by a large foresting company. The project was an experiment on non-native trees like eucalyptus and North American pine. The company began planting these trees 40 years ago then abandoned the project. Like anything that is planted on Brazilian soil the trees grew, with negative effects. Eucalyptus requires a lot moister to grow and removes the nutrients in the soil which neighbouring plants need. The project along with the grounds were left in the care of local civil servants who live inside government owned homes and who must move out once they retire or are no longer working. The locals support the movement because they either understand the encampment is seeking to reclaim the land to make it productive or they have family members who have settled land through MST organization. One of the women we talked to mentioned how she understands the people’s struggle and added,

“When my husband retires we’ll have 90 days to pack our things and move,” she said. “If we can’t find a place we may be moving across the street with [the MST] to get a piece of land.”

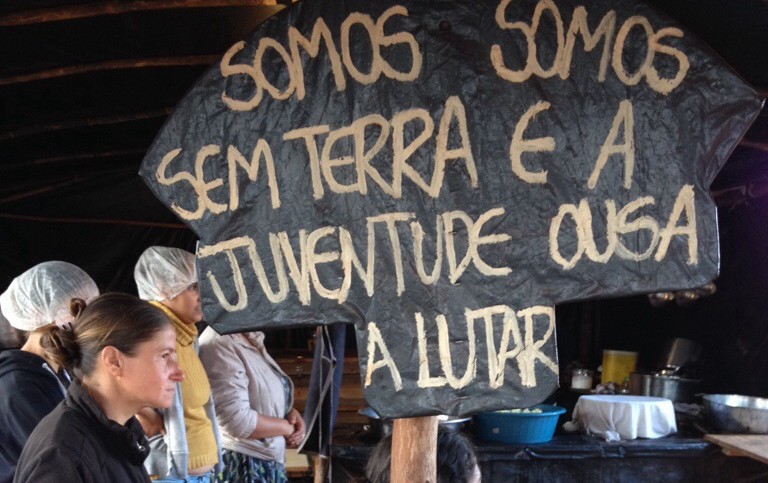

The encampment across the street, while it looks like the usual clean rows of “Barracas” (tents) with a communal kitchen and a headquarter, is particularly unique. It is made of of 450 people primarily composed of children of “assentados” or settled farmers who have received land in the six settlements.

Our guide Tiago tells us that “70 percent of the people here are youth from the neighbouring settlements.” Like most camps, the camp also has families from around the state who are fleeing the crime of the favelas, poverty, poor employment opportunities and lack of services of in the city. But unlike other camps the camp doesn’t lack in supplies because of donations from neighbouring settlements. The camp does lack basic leadership and is not as well organized as the camp we visited in Riberao Preto. During out visits the camp was undergoing a reorganization of leadership as many of the leaders of each nuclei (cluster of homes) and sectors were either unknown to their nucleus or all together absent for most of their duties in the camp. Even when individuals are fined R$20 ($10 CAD) per week if they are absent for their duties this has not improved camp attendance. Of the 450 people on the camp only 200 are currently living here. The camp’s leadership has still not been cemented.

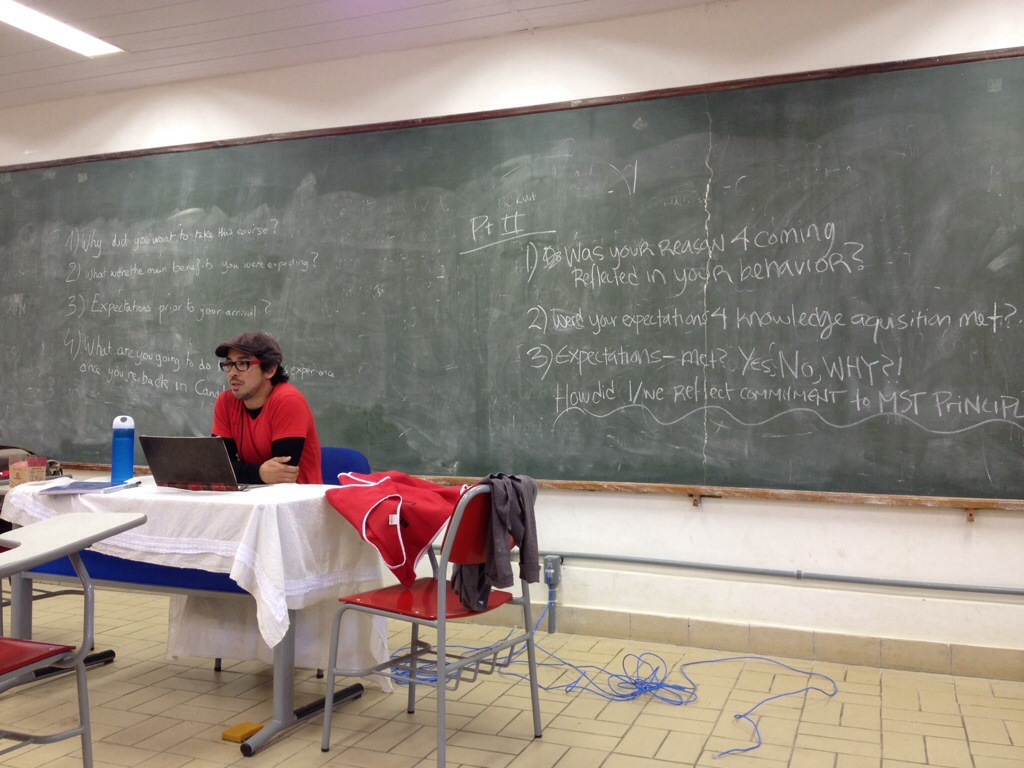

ORGANIZING AN MST CAMP

Part of the MST’s core values is organization from the bottom up. The camps are organized by individual clusters called a “Nucleus.” Each nuclei is lead by a man and a woman and may have hundreds of families per group depending on the size of the camp. In this particular camp six groups were being created made up of people from the same neighbourhoods in each of the six settlements. It was hoped that by grouping people who already knew each other the desire to fulfill the duties assigned each of them received would increase.

Once each nuclei is formed the group begins the process of filling out the necessary positions in each of the camp’s sectors or areas where people are needed. These include but are not limited to:

- Safety—a morning and evening shift

- Sport—in charge of the recreation of the camp an physical activity of the children

- Education—ensures proper schooling is being provided for children and adult literacy classes are organized at night)

- Health—ensures medical supplies are available in the camp and takes care of non life-threatening issues

- Gender—ensures the equal participation of women and men in the organization

- Communication—responsible for talking to the media and are the liaisons between the camp and the MST state leadership

- Infrastructure—responsible for the physical structure of the camp, drainage, electricity, water, etc.

- Production—responsible for producing food for the camp

- Kitchen—responsible of the cooking for all 450 people (this rotates by nuclei and the participation of men is strongly encouraged if men are available during the needed times)

The assignments are handed out by popular suggestion. A person may be selected based on their own personal skills or at the suggestion of others. A person may say, “I have experience in so and so,” to which others agree or suggest someone else better suited for the task. Other times it may be as simple as, “I’ve heard that person is good at this,” or “this person doesn’t have an assignment yet, she’ll be this.” There is no voting on the issue, but a person may decline the assignment in favour of another. However, everyone must have an assignment. The leaders of each nuclei are chosen in this way too.

Once the nuclei are organized the leaders of each group meet together to discuss the coordination of all the sectors an everyone involved. They must create a working and rotating schedule that includes everyone in the camp. Once assignments have been made the leadership seeks for ways to inculcate into its members the MST values of organization and mass participation. The camp assignments and leadership roles are incentives for families seeking to acquire land and serve to create future activitist in the movemement. It is expected that once a family has acquired land they will help other families who have begun the struggle to also acquire land through participation in MST assignments around the country in organizing encampments, providing support in MST actions like marches, road blocks etc, and in national leadership roles in the head quarters in Sao Paulo. Those who are more active in the movement are more likely to acquire land once its available.

As part of the training that goes on in the camp is the modification of past social behaviour like disrespect for rules. The encampment we are visiting has recently experience a breaking of MST patterns: collective agreement on things concerning the camp. The camp has recently received an eviction letter from a judge but it does not contain a date. The camp is in a tense mood and some within the camp have begun discussing among themselves the likelyhood of state repression if the camp is evicted from the eucalyptus farm. Some have begun making cellphone calls to each other trying to organize a large road block to stop the police from coming into the camp. “This, should not happen in this camp!” the people are told by one of the state representatives of the MST during a morning meeting. “If we are going to take any action comrades, it will be done by collective agreement,” she repeats. The camp is told that by not following the MST pattern of discussing everything in the open and excluding people from the discussion puts many in danger. “This camp is organized under the banner of the MST! This camp has to follow the patterns set out by the MST if it is going to succeed!”

The organizing of new nuclei and sectors has mobilized the entire camp. The meetings take about two hours and new assignments are discussed and handed out. At the end we meet up with our guide Tiago who tells us, “Guess who the leader of my nucleus is? Me, again. Nobody else wanted to do it.” The camp leadership is beginning to formalize once more.