I sit back and lay on a hammock five floors up from the ground. It’s midnight in Sao Paulo but it’s 9pm at home. I talk with my family over Skype and I’m ecstatic about seeing their faces–especially the kids. My oldest nephew takes one look at the screen, smiles and exclaims, “Tio you’re as good looking as me!” We all laugh and I tell him I’ve grown up to look just as good as him.

I’ve only been in Brazil for four days yet everyday I’m here I feel more and more like a Brazilian and less and less like a foreigner. The people are incredibly warm and friendly. They comment on my Portuguese and wonder how long I’ve spent speaking it before coming here. They asked me how I learned and I tell them, “Eu aprende o Portuguese vendou novelas,” (I learned Portuguese by watching soap operas). They usually get a good laugh out of this. It’s funny because I learned to understand Portuguese by watching novelas and I learned to read Portuguese by reading the scriptures side by side with my English and Spanish set. If I didn’t know a word in Portuguese I’d look it up in English, then I would look a the Spanish translation and deduce the meaning. I learned the grammar from my teacher Renata. I’m sure she’d be proud to know some people have thought I was a native Brazilian 🙂

Over all I’ve learned, seen and tasted new things that were AMAZING! The other night we went to an all you can eat Pizzeria which served all kinds of clay oven baked pizzas, churrascaria, and desserts pizzas like chocolate and strawberry pizza or sorbet and gelato pizzas. We ate so much and so late at night that all of us had upset stomachs that night. We all got up a random hours because our stomachs hurt so much, but we didn’t complain, in fact we laughed about it the next day as we all struggled to stay awake at church.

The Berleze who I stayed with were excellent hosts. They spoiled me and fed me so much I felt like I was a missionary once again. I’m pretty sure I gave my poor heart quite the scare when I ate two portions of an incredible lasagna yesterday. I’ve loved the fusion of Italian and German cooking that Raquel, the lady of the house cooks. The kids, Daniel, Israel and Miguel (who calls me Vilmar because he can’t remember my name) call me “Tio” meaning uncle. I have been so well received that I’m overwhelmed at how welcoming the Brazilian people are. I loved my time with the Berleze’s!

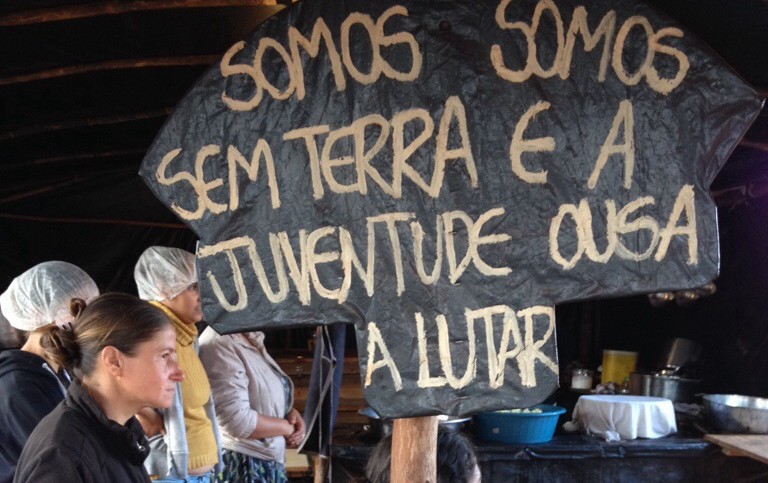

Today I meet my Canadian classmates. I’ll meet my instructor Dan and will begin my Brazilian experience regarding O Movimento Sem-Terra (MST). So far I have gleaned how polemic this group is. To some they are viewed as marginalized people driven to desperate measures. To others they are a group of opportunistic people who are taking advantage of a broken system to gain land they have never or will ever cultivate. People in Sao Paulo know someone who either has encamped in an MST encampment or something similar. With over 1.5 million MST members it’s not hard to find someone who has an opinion about them. The news reports a new encampment in the Eastern sector of the metropolis on a protected forest vital to the water system in the city. The typical black tents made from bamboo frames and black and blue plastic tarps dominate the vegetated park. After being here a few days I can see how people could be driven to such extreme measures.

Two days ago the news reported a real-estate fair that thousands attended. Some attendees camped out in front of the building to be one the lucky ones allowed in hoping to buy a coveted apartment in two new developments. People vied for their “dream home” an apartment with one or two bedrooms going from $75,000 CAD for the most basic. Housing in Sao Paulo is scarce. The city boasts over 11 million inhabitants and the greater metropolis is closer to 20 million—that’s almost the 3/4 of the population of Canada in an area six times the size of Montreal. In Santana, the area I stayed in (located in the north sector of the city), 7 million people call the neighbourhood home. Skyscrapers and condominiums dominate the landscape. Crime is rampant.

Drug gangs, cell phone thieves and corruption are all that the news report. Killings happen everyday in a scale unknown of in Calgary. Security cameras capture bike riding thieves stealing cell phones while people are distracted taking photos or replying to a text message. They capture armed robbers approaching motorists and demanding their phones or else they offer a bullet to the head. People comply and hand their phones over. A news report shows what happened to a teen who didn’t hand his phone over. One minute he was on the phone the other he was on the ground, dead. The bandit made a clear get away with his phone. Death and crime are as common for Paulistas (that’s what the locals call those from Sao Paulo) like hockey and Rick Mercer reports are for Canadians. In the midst of all of this is a continued inflow of immigrants: Korean, Japanese (Sao Paulo boast a high number of Japanese-Brazilians), Haitian and many other Latin Americans from around the southern region. Houses are rare. Most people build up.

The traffic is like nothing I have ever seen–and that’s saying something. I was born in a congested city, Guatemala City, I grew up in Toronto and visited all of the major cities in Canada and the US. I lived in Houston, Texas. I travelled to Mexico City and drove in various places in Mexico. All of these (with the exception of Mexico City and Los Angeles) do not compare to the congestion of Sao Paulo. I left at 6:30am from the apartment to make a 30min ride to the airport (our meeting spot for my school group) and didn’t arrive until 7:45am. I was lucky, I left before rush hour. During holidays a 45 minute drive to the beach drive can turn into an 8 or 12hr drive. The rich don’t worry about traffic, they simply hop on a helicopter and are flown to and from work. I don’t blame them. In a city with such extremes an extreme form of transportation is needed.

The city is incredibly unequal. The rich control the majority of the wealth while the poor make up the majority of the inhabitants. A growing middle-class complains that they make only enough to survive. A friend in Sao Paulo who works for a Brazilian bank handling the financial records of large corporations tells me his experience of being deducted a quarter of his pay on taxes. He pays close to a thousand dollars a month to send his kids to private school because the public system is really bad “muito ruim.” He’s one of the lucky ones. He’s a working professional. Another friend tells me how young men find it hard to get any type of formal education. They must compete with hundreds of thousands for very few coveted spots in the state universities. University education is free in Brazil, if you can get in. Another route is a private institution but that requires money, lots of it.

After becoming aware of all of this I can see why people would turn to encampments to demand that expropriated land by the state be divided between the encamped families for subsistent farming. For many this is the only way they will ever have a piece of land to call home.

I’m exited for the next month. I’m sure I’ll experience a roller coster of emotions as I experience what the poorest in the land struggle with everyday. But like most Brazilians say about life, “Todo bem! Va estar muito legal. Muito bacano.”